K Means Clustering

library(swirl)

swirl()

| Welcome to swirl! Please sign in. If you've been here before, use the same name as

| you did then. If you are new, call yourself something unique.

What shall I call you? Krishnakanth Allika

| Please choose a course, or type 0 to exit swirl.

1: Exploratory Data Analysis

2: Take me to the swirl course repository!

Selection: 1

| Please choose a lesson, or type 0 to return to course menu.

1: Principles of Analytic Graphs 2: Exploratory Graphs

3: Graphics Devices in R 4: Plotting Systems

5: Base Plotting System 6: Lattice Plotting System

7: Working with Colors 8: GGPlot2 Part1

9: GGPlot2 Part2 10: GGPlot2 Extras

11: Hierarchical Clustering 12: K Means Clustering

13: Dimension Reduction 14: Clustering Example

15: CaseStudy

Selection: 12

| Attempting to load lesson dependencies...

| Package ‘ggplot2’ loaded correctly!

| Package ‘fields’ loaded correctly!

| Package ‘jpeg’ loaded correctly!

| Package ‘datasets’ loaded correctly!

| | 0%

| K_Means_Clustering. (Slides for this and other Data Science courses may be found at

| github https://github.com/DataScienceSpecialization/courses/. If you care to use

| them, they must be downloaded as a zip file and viewed locally. This lesson

| corresponds to 04_ExploratoryAnalysis/kmeansClustering.)

...

|== | 2%

| In this lesson we'll learn about k-means clustering, another simple way of examining

| and organizing multi-dimensional data. As with hierarchical clustering, this

| technique is most useful in the early stages of analysis when you're trying to get

| an understanding of the data, e.g., finding some pattern or relationship between

| different factors or variables.

...

|=== | 4%

| R documentation tells us that the k-means method "aims to partition the points into

| k groups such that the sum of squares from points to the assigned cluster centres is

| minimized."

...

|===== | 6%

| Since clustering organizes data points that are close into groups we'll assume we've

| decided on a measure of distance, e.g., Euclidean.

...

|====== | 8%

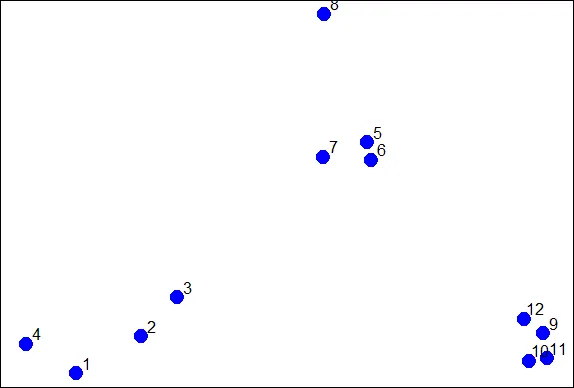

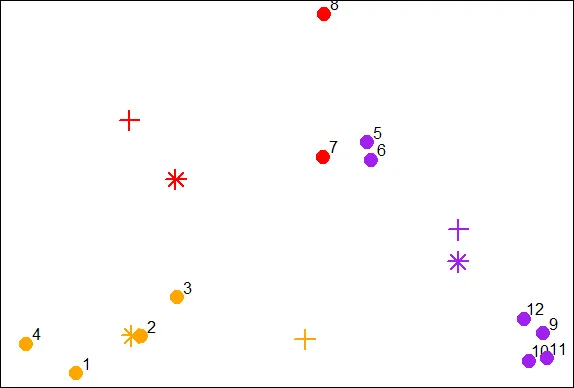

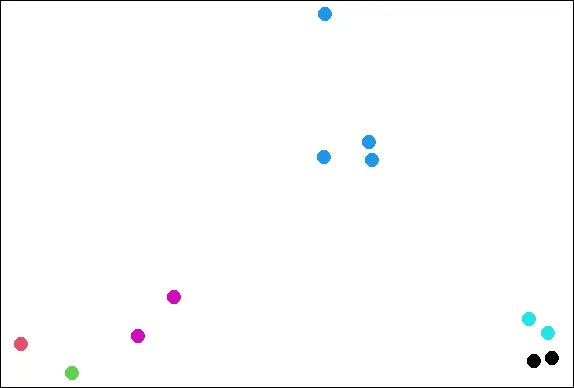

| To illustrate the method, we'll use these random points we generated, familiar to

| you if you've already gone through the hierarchical clustering lesson. We'll

| demonstrate k-means clustering in several steps, but first we'll explain the general

| idea.

...

|======== | 10%

| As we said, k-means is a partioning approach which requires that you first guess how

| many clusters you have (or want). Once you fix this number, you randomly create a

| "centroid" (a phantom point) for each cluster and assign each point or observation

| in your dataset to the centroid to which it is closest. Once each point is assigned

| a centroid, you readjust the centroid's position by making it the average of the

| points assigned to it.

...

|========= | 12%

| Once you have repositioned the centroids, you must recalculate the distance of the

| observations to the centroids and reassign any, if necessary, to the centroid

| closest to them. Again, once the reassignments are done, readjust the positions of

| the centroids based on the new cluster membership. The process stops once you reach

| an iteration in which no adjustments are made or when you've reached some

| predetermined maximum number of iterations.

...

|=========== | 14%

| As described, what does this process require?

1: All of the others

2: A number of clusters

3: A defined distance metric

4: An initial guess as to cluster centroids

Selection: 1

| That's the answer I was looking for.

|============ | 16%

| So k-means clustering requires some distance metric (say Euclidean), a hypothesized

| fixed number of clusters, and an initial guess as to cluster centroids. As

| described, what does this process produce?

1: All of the others

2: An assignment of each point to a cluster

3: A final estimate of cluster centroids

Selection: 1

| You nailed it! Good job!

|============== | 18%

| When it's finished k-means clustering returns a final position of each cluster's

| centroid as well as the assignment of each data point or observation to a cluster.

...

|=============== | 20%

| Now we'll step through this process using our random points as our data. The

| coordinates of these are stored in 2 vectors, x and y. We eyeball the display and

| guess that there are 3 clusters. We'll pick 3 positions of centroids, one for each

| cluster.

...

|================= | 22%

| We've created two 3-long vectors for you, cx and cy. These respectively hold the x-

| and y- coordinates for 3 proposed centroids. For convenience, we've also stored them

| in a 2 by 3 matrix cmat. The x coordinates are in the first row and the y

| coordinates in the second. Look at cmat now.

cmat

[,1] [,2] [,3]

[1,] 1 1.8 2.5

[2,] 2 1.0 1.5

| Excellent work!

|================== | 24%

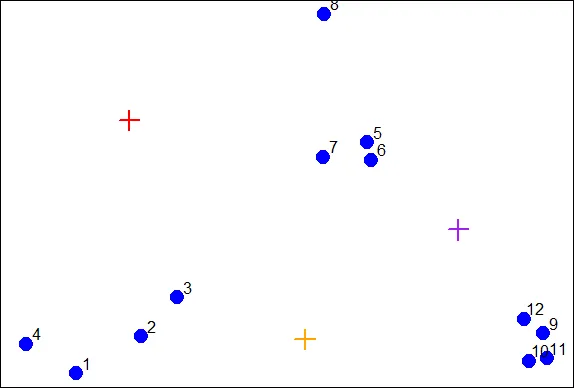

| The coordinates of these points are (1,2), (1.8,1) and (2.5,1.5). We'll add these

| centroids to the plot of our points. Do this by calling the R command points with 6

| arguments. The first 2 are cx and cy, and the third is col set equal to the

| concatenation of 3 colors, "red", "orange", and "purple". The fourth argument is pch

| set equal to 3 (a plus sign), the fifth is cex set equal to 2 (expansion of

| character), and the final is lwd (line width) also set equal to 2.

points(cx,cy,col=c("red","orange","purple"),pch=3,cex=2,lwd=2)

| You nailed it! Good job!

|==================== | 26%

| We see the first centroid (1,2) is in red. The second (1.8,1), to the right and

| below the first, is orange, and the final centroid (2.5,1.5), the furthest to the

| right, is purple.

...

|====================== | 28%

| Now we have to calculate distances between each point and every centroid. There are

| 12 data points and 3 centroids. How many distances do we have to calculate?

1: 15

2: 108

3: 36

4: 9

Selection: 3

| You are amazing!

|======================= | 30%

| We've written a function for you called mdist which takes 4 arguments. The vectors

| of data points (x and y) are the first two and the two vectors of centroid

| coordinates (cx and cy) are the last two. Call mdist now with these arguments.

mdist(x,y,cx,cy)

[,1] [,2] [,3] [,4] [,5] [,6] [,7] [,8]

[1,] 1.392885 0.9774614 0.7000680 1.264693 1.1894610 1.2458771 0.8113513 1.026750

[2,] 1.108644 0.5544675 0.3768445 1.611202 0.8877373 0.7594611 0.7003994 2.208006

[3,] 3.461873 2.3238956 1.7413021 4.150054 0.3297843 0.2600045 0.4887610 1.337896

[,9] [,10] [,11] [,12]

[1,] 4.5082665 4.5255617 4.8113368 4.0657750

[2,] 1.1825265 1.0540994 1.2278193 1.0090944

[3,] 0.3737554 0.4614472 0.5095428 0.2567247

| Excellent job!

|========================= | 32%

| We've stored these distances in the matrix distTmp for you. Now we have to assign a

| cluster to each point. To do that we'll look at each column and ?

1: add up the 3 entries.

2: pick the minimum entry

3: pick the maximum entry

Selection: 2

| Perseverance, that's the answer.

|========================== | 34%

| From the distTmp entries, which cluster would point 6 be assigned to?

1: none of the above

2: 3

3: 2

4: 1

Selection: 2

| Keep working like that and you'll get there!

|============================ | 36%

| R has a handy function which.min which you can apply to ALL the columns of distTmp

| with one call. Simply call the R function apply with 3 arguments. The first is

| distTmp, the second is 2 meaning the columns of distTmp, and the third is which.min,

| the function you want to apply to the columns of distTmp. Try this now.

apply(distTmp,2,which.min)

[1] 2 2 2 1 3 3 3 1 3 3 3 3

| You are really on a roll!

|============================= | 38%

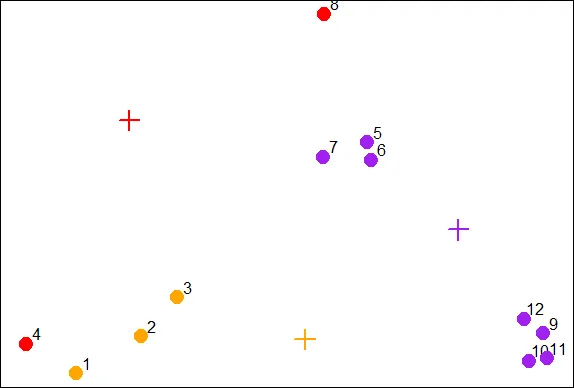

| You can see that you were right and the 6th entry is indeed 3 as you answered

| before. We see the first 3 entries were assigned to the second (orange) cluster and

| only 2 points (4 and 8) were assigned to the first (red) cluster.

...

|=============================== | 40%

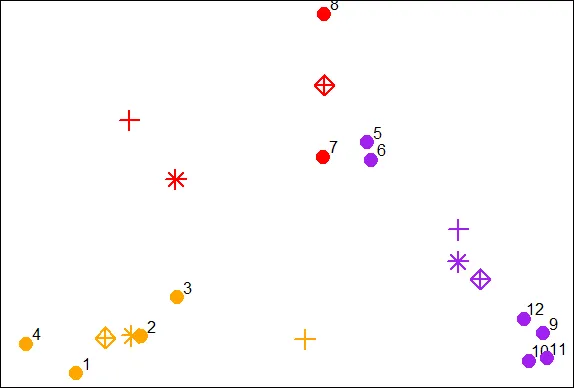

| We've stored the vector of cluster colors ("red","orange","purple") in the array

| cols1 for you and we've also stored the cluster assignments in the array newClust.

| Let's color the 12 data points according to their assignments. Again, use the

| command points with 5 arguments. The first 2 are x and y. The third is pch set to

| 19, the fourth is cex set to 2, and the last, col is set to cols1[newClust].

points(x,y,pch=19,cex=2,col=cols1[newClust])

| Keep up the great work!

|================================ | 42%

| Now we have to recalculate our centroids so they are the average (center of gravity)

| of the cluster of points assigned to them. We have to do the x and y coordinates

| separately. We'll do the x coordinate first. Recall that the vectors x and y hold

| the respective coordinates of our 12 data points.

...

|================================== | 44%

| We can use the R function tapply which applies "a function over a ragged array".

| This means that every element of the array is assigned a factor and the function is

| applied to subsets of the array (identified by the factor vector). This allows us to

| take advantage of the factor vector newClust we calculated. Call tapply now with 3

| arguments, x (the data), newClust (the factor array), and mean (the function to

| apply).

tapply(x,newClust,mean)

1 2 3

1.210767 1.010320 2.498011

| Perseverance, that's the answer.

|=================================== | 46%

| Repeat the call, except now apply it to the vector y instead of x.

tapply(y,newClust,mean)

1 2 3

1.730555 1.016513 1.354373

| Your dedication is inspiring!

|===================================== | 48%

| Now that we have new x and new y coordinates for the 3 centroids we can plot them.

| We've stored off the coordinates for you in variables newCx and newCy. Use the R

| command points with these as the first 2 arguments. In addition, use the arguments

| col set equal to cols1, pch equal to 8, cex equal to 2 and lwd also equal to 2.

points(newCx,newCy,col=cols1,pch=8,cex=2,lwd=2)

| Keep up the great work!

|====================================== | 50%

| We see how the centroids have moved closer to their respective clusters. This is

| especially true of the second (orange) cluster. Now call the distance function mdist

| with the 4 arguments x, y, newCx, and newCy. This will allow us to reassign the data

| points to new clusters if necessary.

mdist(x,y,newCx,newCy)

[,1] [,2] [,3] [,4] [,5] [,6] [,7] [,8]

[1,] 0.98911875 0.539152725 0.2901879 1.0286979 0.7936966 0.8004956 0.4650664 1.028698

[2,] 0.09287262 0.002053041 0.0734304 0.2313694 1.9333732 1.8320407 1.4310971 2.926095

[3,] 3.28531180 2.197487387 1.6676725 4.0113796 0.4652075 0.3721778 0.6043861 1.643033

[,9] [,10] [,11] [,12]

[1,] 3.3053706 3.282778 3.5391512 2.9345445

[2,] 3.5224442 3.295301 3.5990955 3.2097944

[3,] 0.2586908 0.309730 0.3610747 0.1602755

| Excellent work!

|======================================== | 52%

| We've stored off this new matrix of distances in the matrix distTmp2 for you. Recall

| that the first cluster is red, the second orange and the third purple. Look closely

| at columns 4 and 7 of distTmp2. What will happen to points 4 and 7?

1: They will both change to cluster 2

2: Nothing

3: They're the only points that won't change clusters

4: They will both change clusters

Selection: 4

| You nailed it! Good job!

|========================================== | 54%

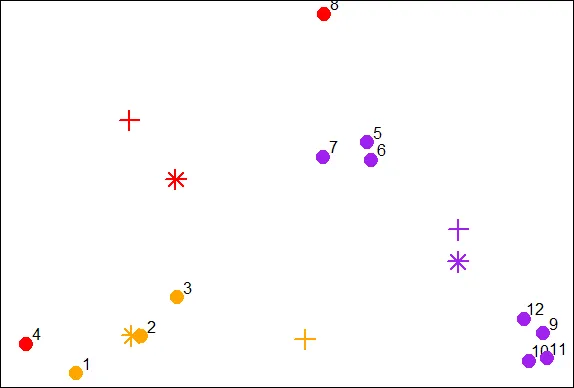

| Now call apply with 3 arguments, distTmp2, 2, and which.min to find the new cluster

| assignments for the points.

apply(distTmp2,2,which.min)

[1] 2 2 2 2 3 3 1 1 3 3 3 3

| That's a job well done!

|=========================================== | 56%

| We've stored off the new cluster assignments in a vector of factors called

| newClust2. Use the R function points to recolor the points with their new

| assignments. Again, there are 5 arguments, x and y are first, followed by pch set to

| 19, cex to 2, and col to cols1[newClust2].

points(x,y,pch=19,cex=2,col=cols1[newClust2])

| Keep working like that and you'll get there!

|============================================= | 58%

| Notice that points 4 and 7 both changed clusters, 4 moved from 1 to 2 (red to

| orange), and point 7 switched from 3 to 2 (purple to red).

...

|============================================== | 60%

| Now use tapply to find the x coordinate of the new centroid. Recall there are 3

| arguments, x, newClust2, and mean.

tapply(x,newClust2,mean)

1 2 3

1.8878628 0.8904553 2.6001704

| You're the best!

|================================================ | 62%

| Do the same to find the new y coordinate.

tapply(y,newClust2,mean)

1 2 3

2.157866 1.006871 1.274675

| Excellent work!

|================================================= | 64%

| We've stored off these coordinates for you in the variables finalCx and finalCy.

| Plot these new centroids using the points function with 6 arguments. The first 2 are

| finalCx and finalCy. The argument col should equal cols1, pch should equal 9, cex 2

| and lwd 2.

points(finalCx,finalCy,col=cols1,pch=9,cex=2,lwd=2)

| You nailed it! Good job!

|=================================================== | 66%

| It should be obvious that if we continued this process points 5 through 8 would all

| turn red, while points 1 through 4 stay orange, and points 9 through 12 purple.

...

|==================================================== | 68%

| Now that you've gone through an example step by step, you'll be relieved to hear

| that R provides a command to do all this work for you. Unsurprisingly it's called

| kmeans and, although it has several parameters, we'll just mention four. These are

| x, (the numeric matrix of data), centers, iter.max, and nstart. The second of these

| (centers) can be either a number of clusters or a set of initial centroids. The

| third, iter.max, specifies the maximum number of iterations to go through, and

| nstart is the number of random starts you want to try if you specify centers as a

| number.

...

|====================================================== | 70%

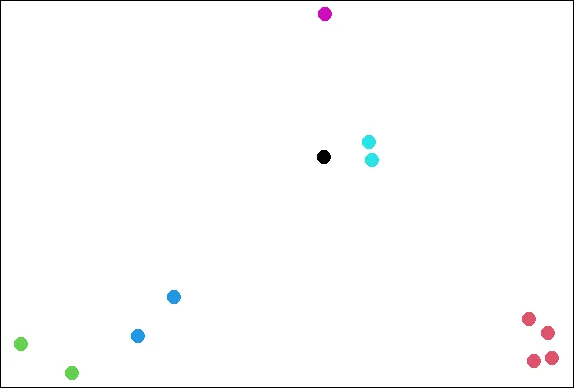

| Call kmeans now with 2 arguments, dataFrame (which holds the x and y coordinates of

| our 12 points) and centers set equal to 3.

kmeans(dataFrame,centers=3)

K-means clustering with 3 clusters of sizes 4, 4, 4

Cluster means:

x y

1 0.8904553 1.0068707

2 2.8534966 0.9831222

3 1.9906904 2.0078229

Clustering vector:

[1] 1 1 1 1 3 3 3 3 2 2 2 2

Within cluster sum of squares by cluster:

[1] 0.34188313 0.03298027 0.34732441

(between_SS / total_SS = 93.6 %)

Available components:

[1] "cluster" "centers" "totss" "withinss" "tot.withinss"

[6] "betweenss" "size" "iter" "ifault"

| You are really on a roll!

|======================================================= | 72%

| The program returns the information that the data clustered into 3 clusters each of

| size 4. It also returns the coordinates of the 3 cluster means, a vector named

| cluster indicating how the 12 points were partitioned into the clusters, and the sum

| of squares within each cluster. It also shows all the available components returned

| by the function. We've stored off this data for you in a kmeans object called kmObj.

| Look at kmObj$iter to see how many iterations the algorithm went through.

kmObj$iter

[1] 1

| You got it!

|========================================================= | 74%

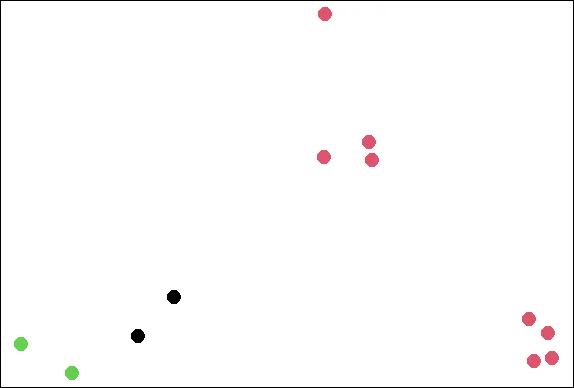

| Two iterations as we did before. We just want to emphasize how you can access the

| information available to you. Let's plot the data points color coded according to

| their cluster. This was stored in kmObj$cluster. Run plot with 5 arguments. The

| data, x and y, are the first two; the third, col is set equal to kmObj$cluster, and

| the last two are pch and cex. The first of these should be set to 19 and the last to

| 2.

plot(x,y,col=kmObj$cluster,pch=19,cex=2)

| You are doing so well!

|=========================================================== | 76%

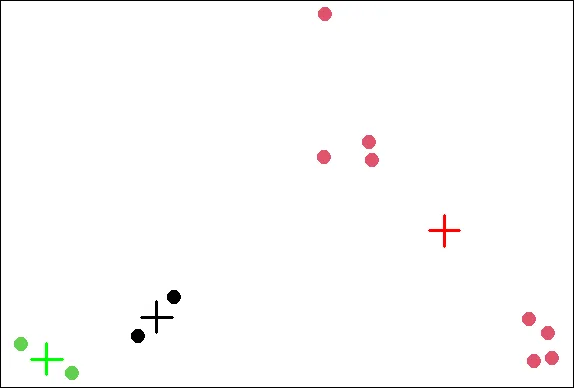

| Now add the centroids which are stored in kmObj$centers. Use the points function

| with 5 arguments. The first two are kmObj$centers and col=c("black","red","green").

| The last three, pch, cex, and lwd, should all equal 3.

points(kmObj$centers,col=c("black","red","green"),pch=3,cex=3,lwd=3)

| Excellent work!

|============================================================ | 78%

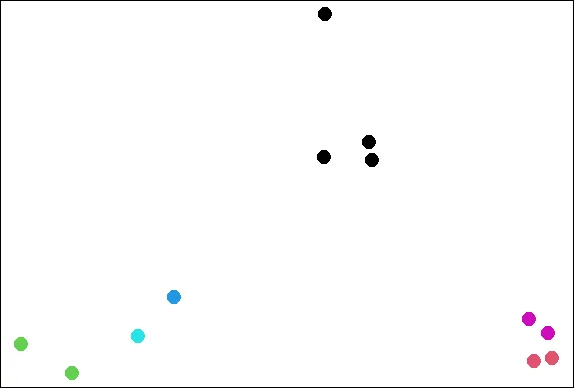

| Now for some fun! We want to show you how the output of the kmeans function is

| affected by its random start (when you just ask for a number of clusters). With

| random starts you might want to run the function several times to get an idea of the

| relationships between your observations. We'll call kmeans with the same data points

| (stored in dataFrame), but ask for 6 clusters instead of 3.

...

|============================================================== | 80%

| We'll plot our data points several times and each time we'll just change the

| argument col which will show us how the R function kmeans is clustering them. So,

| call plot now with 5 arguments. The first 2 are x and y. The third is col set equal

| to the call kmeans(dataFrame,6)$cluster. The last two (pch and cex) are set to 19

| and 2 respectively.

plot(x,y,col=kmeans(dataFrame,6)$cluster,pch=19,cex=2)

| You nailed it! Good job!

|=============================================================== | 82%

| See how the points cluster? Now recall your last command and rerun it.

plot(x,y,col=kmeans(dataFrame,6)$cluster,pch=19,cex=2)

| Nice work!

|================================================================= | 84%

| See how the clustering has changed? As the Teletubbies would say, "Again! Again!"

plot(x,y,col=kmeans(dataFrame,6)$cluster,pch=19,cex=2)

| That's the answer I was looking for.

|================================================================== | 86%

| So the clustering changes with different starts. Perhaps 6 is too many clusters?

| Let's review!

...

|==================================================================== | 88%

| True or False? K-means clustering requires you to specify a number of clusters

| before you begin.

1: False

2: True

Selection: 2

| You nailed it! Good job!

|===================================================================== | 90%

| True or False? K-means clustering requires you to specify a number of iterations

| before you begin.

1: True

2: False

Selection: 2

| You got it right!

|======================================================================= | 92%

| True or False? Every data set has a single fixed number of clusters.

1: False

2: True

Selection: 1

| Excellent job!

|======================================================================== | 94%

| True or False? K-means clustering will always stop in 3 iterations

1: True

2: False

Selection: 2

| You are really on a roll!

|========================================================================== | 96%

| True or False? When starting kmeans with random centroids, you'll always end up with

| the same final clustering.

1: False

2: True

Selection: 1

| Great job!

|=========================================================================== | 98%

| Congratulations! We hope this means you found this lesson oK.

...

|=============================================================================| 100%

| Would you like to receive credit for completing this course on Coursera.org?

1: No

2: Yes

Selection: 2

What is your email address? xxxxxx@xxxxxxxxxxxx

What is your assignment token? xXxXxxXXxXxxXXXx

Grade submission succeeded!

| Excellent work!

| You've reached the end of this lesson! Returning to the main menu...

| Please choose a course, or type 0 to exit swirl.

1: Exploratory Data Analysis

2: Take me to the swirl course repository!

Selection: 0

| Leaving swirl now. Type swirl() to resume.

rm(list=ls())

Last updated 2020-10-02 01:20:12.461303 IST

Comments